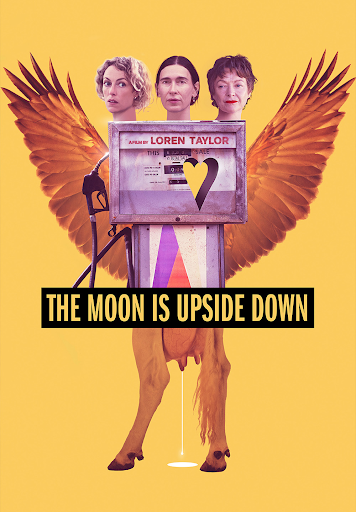

Some creative partnerships feel engineered. Others feel like gravitational accidents - two bodies colliding, rearranging the air around them. The Moon Is Upside Down is one such cosmic event.

There are collaborations in cinema that announce themselves loudly – orchestrated, negotiated, strategically aligned. And then there are the rare ones, the collisions of instinct and electricity, where two artists move toward each other as if drawn by something tidal.

The Moon Is Upside Down belongs to the latter. It is stitched from silence, grief, and the trembling beauty of connection, built by two women who know how to bend narrative gravity: writer–director–actor Loren Taylor, and legendary performer Elizabeth Hawthorne.

Taylor constructs the world. Hawthorne breathes life into its shadows. What emerges is not simply a film but a pulse.

The Woman Who Built Her Own Orbit - Loren Taylor

Loren Taylor feels like someone who doesn’t wait for permission. She writes, directs, performs – then detonates expectation with unnerving calm.

Her three creative selves don’t collide, she says; they negotiate, tussle, argue until “something truthful claws its way out.”

Her film is woven from “invisible threads” – loneliness, connection, the everyday collisions that bruise and heal us. These threads pulse beneath the script from the first word, and Taylor follows them with something close to instinct.

To work with Elizabeth Hawthorne, she says, was “like dancing with fire.” Two performers with knives – sharp, controlled, dangerously precise.

As for what defines a New Zealand story? Taylor doesn’t align herself with the clichés. It’s not landscape or accent, but a refusal – the refusal to explain ourselves to anyone outside the room.

What she’s working on next remains private. But it burns. You can feel the heat radiating off her orbit.

5 Questions with Loren Taylor

Writer/Director of The Moon Is Upside Down – now streaming on Amazon Prime Channels via Rialto

Some filmmakers build worlds. Loren Taylor tunes into them – quietly, acutely, as if she’s listening for a frequency most of us don’t notice. The Moon Is Upside Down, her debut feature as writer and director, feels like it was crafted from that wavelength: intimate, otherworldly, and deeply attuned to the interior lives of its characters.

Taylor works with precision but never rigidity. Her filmmaking is instinctive, anchored in emotional truth rather than spectacle. She doesn’t push performances; she invites them. And with Elizabeth Hawthorne at the centre, that invitation becomes something rare – a creative partnership defined by trust and fearlessness.

Where Hawthorne speaks of Faith “gaining life for the first time,” Taylor frames the story as an exploration of the quiet shifts that change us: the unspoken moments, the near–miss connections, the choices that break us open. Her camera lingers, not to analyse, but to witness.

In this edition of ViewMag, Loren talks about the strange magic of building a world from silence, how she approaches character as a living organism, and why the film needed to unfold the way a bruise does: slowly, painfully, and with unexpected beauty.

She doesn’t direct for effect.

She directs for truth.

And in The Moon Is Upside Down, that truth lands with a softness that still leaves a mark.

(I can die happy reading this intro, Roger!)

- Director, writer, and star-three crowns, one head. How did you keep them from colliding?

Did one voice dominate or did they all argue in the same room until something truthful clawed its way out?

I’m all for collusions in a creative process. The Big Bang gave birth to something that ended up creating the octopus, the orchid, the star-nosed mole…. maybe a few rocks/crowns/heads whacking into each other is a good starting point?! Or not. On reflection do I think it was crazy to have jammed three crowns on my head? Yes and no. I think writing and directing is compatible, but directing yourself is a bit bonkers. The writer and the director got on very well – they are great friends. I think the actor might have thought the director was paying more attention to the crew and the other actors rather than giving her as much direction as she would have liked, and the director might have liked it if the actor was a bit more focussed in some of her scenes. My deepest wish was to make sure that what we were creating felt truthful and I was surrounded by brilliant collaborators in that pursuit.

- The film feels woven from invisible thread—loneliness, connection, the small collisions that make us human. did you sense that pulse from the first word on the page?

Or did it emerge slowly, like a bruise under skin?

Because I began the writing process with two of my sister, Anna Taylor’s, short stories (from her award winning collection Relief) open beside me, I was lucky to start with something that already had a pulse. And the reason I was attracted to her work is because tonally (maybe its genetic) I am drawn to art that speaks to all those things you have so poetically listed. And I love that you used the word bruise. I think all the characters are bruised (find me a human who isn’t or hasn’t been at some point in their lives). I knew that I wanted to make a film honouring vulnerability, loneliness, and fallibility – pointing to how we might find relief when we turn to face what we are avoiding. A quote that has stayed with me that relates to this is ‘Pay attention to what life is trying to reveal to you‘. I love that line.

And the weaving happened in collaboration – with Anna, Glen Maw – another early key collaborator and wonderful creative mind, through conversations with my dear producers George Conder and Philippa Campbell, skilled script friends and my Mum (it’s a family affair). And from time alone staring out the window or lying on the floor looking at the ceiling and watching the spiders (the master weavers), waiting to catch a thread.

3. Working with Elizabeth Hawthorne must have felt like dancing with fire. how did that collaboration shape what we see on screen?

Two performers with precision knives, cutting emotion to the bone—did she ever make you flinch?

She is fire! And water and earth and metal. I love her. She is a remarkable actress. Her interior world is electrifying – she is sensitive, brave and such a great clown. I felt like I was working with a concert pianist – technically extraordinary and able to let herself be taken over by the moment and just feel. She entered Faith utterly and sprinted through our unforgiving schedule without wavering. She worked deeply and fearlessly despite significant low-budget film-making obstacles – lack of time and all manner of discomforts. Elizabeth gave Faith a cool steeliness and then, just under the skin, so much longing.

I was never more grateful to Elizabeth than in the long driving scene between Faith and Natalia in the car. We had closed the road but it wasn’t filmed on a low loader so we required Elizabeth to drive the car with a huge camera rig on the bonnet. Technically it’s a huge ask, cornering gently, maintaining an even speed, avoiding looking down the barrel of the camera while needing to look ahead of her at the road! A hellish task. She did all that while playing the delicate emotional music required in the scene – that was many, many pages! So grateful to her for being able to make what she was doing technically vanish and all that is on screen is a woman being quietly unravelled by a conversation with a stranger. She’s a master.

4. What defines a kiwi story to you now?

Is it landscape, silence, humour that hides heartbreak? Or is it the refusal to explain ourselves to anyone outside the room?

I think humour that hides heartbreak is a good bet!

The first NZ film I saw at the cinema was The Navigator. I’ll never forget it – I fell in love with the boy and the art form. And then The Quiet Earth. And then The Piano and Once were Warriors. So perhaps landscape is a common thread there? I’m lucky enough to work with screenwriters on their scripts at Story Camp Aotearoa (a Script to Screen film lab) and, in the years that I’ve been doing it, I feel like we are seeing more and more wildly diverse voices and stories. It’s exciting.

- What are you working on next, and does it burn with the same strange gravity?

Because after the moon is upside down, one thing’s certain—you won’t orbit quietly.

I’m writing a TV show and a film, both with my sister. I hope they burn with something, and I hope they are a bit strange – I love strange art that burns/warms/lights up and casts shadows.

Have you read Orbital by Samantha Harvey? There is a section where a character talks about a space walk and the impulse, that is common among astronauts (which they must override!) to cut the chord and float into the mysterious body of the universe. I loved that. It resonated. I think I am more and more interested in listening to primal impulses when it comes to the creative process. I feel very lucky to have the chance to make more work.

Gravity, Interrupted

Loren Taylor doesn’t tell stories. She bends them. Twists them until they point somewhere new. Watch her. She’s not just part of New Zealand cinema—she’s shifting its axis.

The Woman Who Knows When the Light Shifts - Elizabeth Hawthorne

Elizabeth Hawthorne doesn’t simply enter a room – she alters its molecules. There is something surgical behind her gaze: a scalpel of intelligence that slices through performance and exposes the living truth beneath.

As Faith, she walks the impossible line between grief and the frail, flickering instinct toward survival. Her grief, she says, is “always just below the surface.” Not performed. Lived.

Through Rita – a marginalised woman shadowed by invisibility – Faith discovers something paradoxical: that death can open the door to vitality. “Through Rita’s death,” Hawthorne says, “Faith gains, for the first time, life.”

When the camera stops, the ache doesn’t. The film continues “in the bones,” in the unconscious, in the marrow of the work.

Restlessness drives her; applause doesn’t. She chases danger – the responsibility to creator, story, and audience. She trusts quiet more than dialogue. “Words can lie. Stillness never does.”

And yes, Faith follows her home. The vital characters always do.

“The camera never really stops; it keeps

whirring in the bones.” – Elizabeth Hawthorne

5 questions with Elizabeth Hawthorne

- The film walks a line between grief and survival. how do you step into a

character living with loss without drowning in it? Is it instinct, or is it surgery?

Do you dissect her pain until only the truth remains, or do you let it swallow you whole and hope to crawl out alive?

Well I think Faith is drowning in her grief and loss of a life not lived, in that her grief and loss are constant, always just below the surface, I think Faith is conscious of these feelings , but as yet can’t identify them specifically, however through her meeting Rita , Faith begins to recognise her actual Self through caring for this other person. It is paradoxical that through the death of Rita; a marginalised, isolated woman, that Faith gains true connection and survival. Through Rita’s Death, Faith gains, for the first time, Life. This is the pathway Loren has created for Faith so that Faith does emerge vitally alive.

- The moon is upside down feels haunted, but not by ghosts. what lingers for

you after the cameras stop?

Does the ache stay in the bones, or do you leave it hanging on the set like a forgotten coat?

All the people who inhabit The Moon is Upside Down are consumed by their individual quests and these quests certainly do take them over, so the camera never really stops; it is whirring away in the minds and feelings and in the unconscious and as you say , ‘in the bones’ certainly during the time of making the film and the resonances are forever there .

- You’ve worked through decades of New Zealand theatre and film. what keeps

you restless?

A script. What has someone created? What am I going to find out?

There must be a point where craft turns to hunger. Where applause is just noise, and what you’re really chasing is danger.

Yes, I think that is true, because it is terrifying work. Every project indicates danger/risk in many aspects; personal, professional, responsibility to the project, the creator, the investors, the audience. It is weighty. I suppose it is dangerous work to undertake, to form a ‘contract’, to take the risks, to understand what they are and to take them on.

- there’s a moment in the film when silence does all the speaking. do you trust

quiet more than dialogue?

Words can lie. Stillness never does.

Yes, I trust quiet more than dialogue. Loren has a keen awareness of the eloquence of Silence. How silence contains more than can be expressed in words. More potent. Loren uses this awareness poetically and incisively.

- when the curtain falls, who do you return to, yourself, or the shadow you’ve

just lived inside?

And does she follow you home?

Yes, most definitely Faith fascinated me from the first reading, she increasingly revealed herself and became more and more present. I felt in close contact with her and her life, I still do.

There are certain characters created by writers that are so vital/complex that they remain a visceral part of oneself.

Why This Film Matters

There are films that simply join the cultural noise – another title, another thumbnail – and then there are films that feel like a recalibration. A soft but certain shift in how we understand the world, and ourselves inside it.

The Moon Is Upside Down is the latter.

It matters because it treats silence not as absence, but as architecture.

Because it trusts its audience to feel instead of be told.

Because in an era addicted to spectacle, it dares to be intimate.

Loren Taylor builds a world that vibrates at a lower frequency – tender, bruised, unfashionably human – yet it’s in that softness that the film finds its power. Her storytelling bends toward empathy without sentimentality, precision without coldness. It is the work of someone who knows that the smallest collisions between people can be the loudest.

And Elizabeth Hawthorne… she reminds us what a performance can do when it steps away from performance. Her Faith is so lived-in, so unguarded, that we recognise ourselves in the cracks – the grief we don’t name, the hope we don’t admit to wanting. Watching her is like watching someone open a window in a dark room.

This film matters because it is unmistakably ours – not in the way we often declare New Zealand stories, through landscape or lore, but through emotional topography. Through refusal. Through the confidence to leave things unsaid.

It matters because it lingers.

And in a world of fleeting attention, anything that lingers is worth holding onto.

Loren Taylor doesn’t tell stories – she bends them.

Elizabeth Hawthorne doesn’t play characters – she inhabits them.

Together, they twist the axis of New Zealand cinema.

The Moon Is Upside Down doesn’t simply unfold.

It lingers.

It hums.

THE MOON IS UPSIDE DOWN – Now streaming on Amazon Prime, and Rialto Film.

— Roger Wyllie, View Mag

Rialto is streaming now!

Join now and start your 7-day free trial